'BUT' BOOK TOUR OF THE UK

And that’s the end of fourteen book events in fifteen days around the UK – fascinating, heartening and reassuring.

Fascinating because doing something absolutely alone is new to me. Whether in a band – off to the left, backing vocals and occasional between-song chatter, or in the audience for a musical/play, or hovering beside confident partners, or waving my arms around in front of a choir (and significantly, with my back to the audience) – I’ve never liked the idea of being a solo performer. Even the word ‘performer’ feels completely weird to me.

But this book, ‘But’, it celebrates the idea of disruption, including disrupting your own ingrained patterns. Being fearless of failure. So it made sense to have a go at sitting in front of audiences and talking, singing, reading, and seeing what could happen. It isn’t that I was particularly afraid of being alone in front of people, just that I had told myself over the years that “that’s not what you do”.

In Chumbawamba I could always rely on Dunst, Alice and Danbert to act out the leading roles, to do the thing that they were so good at. And I loved being in the half-shadows with Lou, Harry, Jude, Neil, Paul and the rest. But writing a book really is a solo affair, just me and my words all twisted up in Christian Brett’s amazing typography. And I’ve discovered on this UK tour around some of the loveliest, friendliest bookshops that the book, the printed slab of pages, is the thing to hide behind. That and the songs.

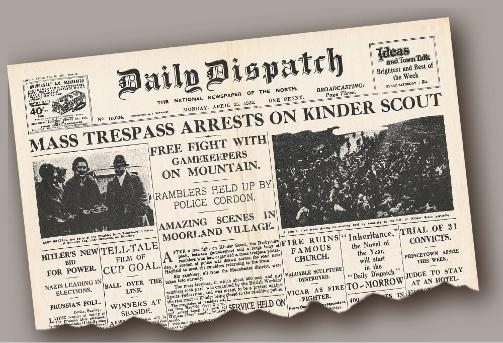

The songs, picked from 40-odd years of songwriting (I mean, shit, that sounds ridiculous. Like I must have started writing songs during the Victorian era or something) are such a stable, dependable crutch to rely on. They were written to annotate the times, written to comment on the world around us at that time. But – they’re still relevant, because while culture and society has slowly, gradually crept forwards, politics has gone into reverse, in some cases right back to the 1930s.

But the concerts/events/shows (none of these words describe those heartwarming gatherings of forty or fifty people in bookshops) have been uplifting and hopeful, even if they’re just a physical gathering of open-minded folk in a welcoming space. And that’s a big part of what we need right now – to gather, physically. To be present, together, and not just on a screen with a keyboard.

I can’t single out events that were more ‘special’ than other events, because they were all great in their various ways. And all full! And I’ve loved finding out that the legacy of Chumbawamba is still out there, still important to so many people (it was a treat to sing with Lou and Dunst in Farsley and Brighton). I didn’t think I’d ever sing some of those old songs again, but it’s been a privilege to play them – especially as they are now so relevant (again).

To all the venues, bookshops and spaces that hosted this thing, all I can say is a huge thank you. To the wider world of culture, society and politics, all I can say is a massive STAY INFORMED, STAY HOPEFUL, HAVE FUN, and KILL FASCISTS.

"DESIGN IS THINKING MADE VISUAL." (Saul Bass)

February 2025

When I was still in my teens, my schoolboy-punk-bandmate friend Nadeem suddenly moved to the USA. This happened almost overnight – Nadeem said, “our family is moving to Florida. Next week. Don’t tell anybody.” This was obviously some sort of dodgy escaping-the-law move that we were never privy to, but there it was, he disappeared.

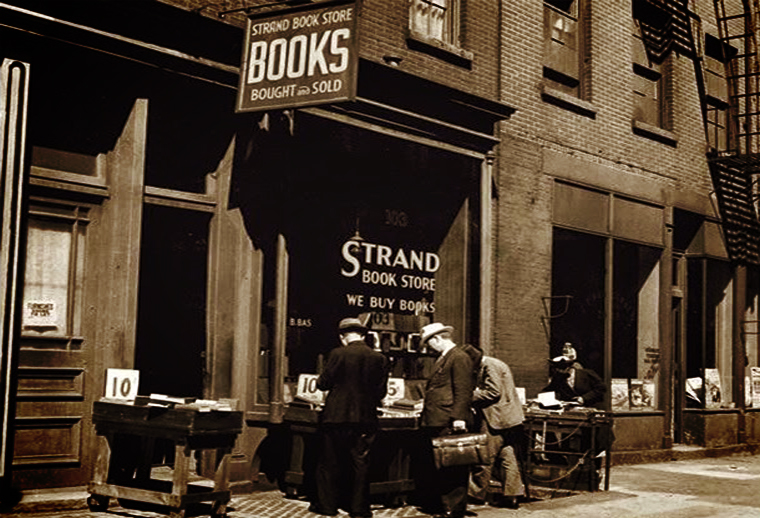

A year later, having saved enough money from part-time jobs and dole cheques, me and my friends bought plane tickets to visit him. And then, somehow, we were in the States, sleeping in the dodgiest New York hotels and going to see Bad Brains, reading a book of Lenny Bruce sketches and walking up to Lexington 125. I bought two second-hand paperbacks from the Strand bookstore on Broadway – Marshall McLuhan’s ‘The Medium is the Message’ and Jerry Rubin’s ‘Do It!’.

The McLuhan book had an image of a woman on the front cover wearing a dress that was emblazoned with the word ‘LOVE’, and the middle section of the ‘O’ of love was cut out to reveal her bellybutton. Inside the book, the text was interrupted and annotated by type, typography, images, anything to break up the standard format of a book.

The Jerry Rubin book was the same. Text running all over the place, getting softer or LOUDER as the ideas in the book allowed or suggested. Both books became my bibles for a while. I’d been escaping from the King James version for many years, but here I found some semblance of sacred texts, not only in the ideas but in the presentation of those ideas.

Decades later (now!) deciding to write ‘But’, I knew all along that it was never going to be a neat ‘n’ tidy perfectly-formatted book. And as it happens, I knew the only person who would be able to tap into that Marshall McLuhan/Jerry Rubin world and make typographical sense of it. Actually I didn’t just know him, I sat next to him at the football every fortnight.

Christian Brett – aka Bracketpress – is obsessed by typography. He’s worked extensively with Penny Rimbaud of Crass, with Killing Joke and with Sleaford Mods. He plays with words – printed words – in a way that reminds me of those ground-breaking books I read all those years ago, books where the design of the words complemented the meaning of the words.

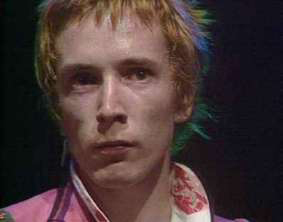

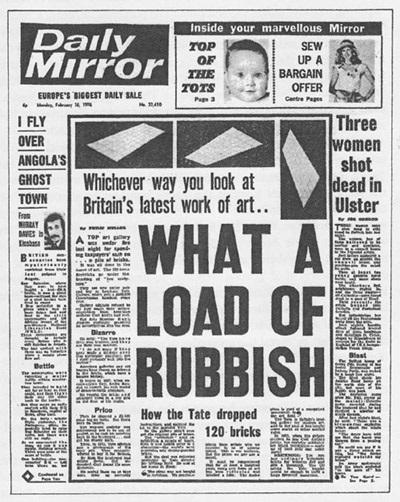

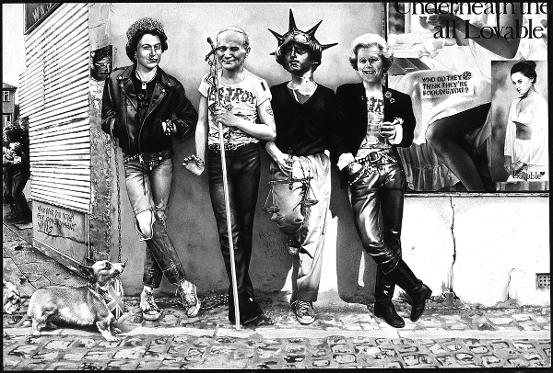

Words are important. The look of words is important. I remember those stark ‘Frankie Says’ T-shirts – suitably, they used a font called IMPACT. British railways used a reliable, readable and somehow dependable font called Gill Sans. Jamie Reid’s cut-up blackmail note lettering for the Sex Pistols spelled out danger and chaos. Anarchist punk band Crass coupled Gee Vaucher’s monochrome pencil-collages with harsh typewriter and stencil lettering. It hit you in the face with its starkness and it chimed with the brutalist 1970s concrete-city-centre architecture of the time.

When Chumbawamba first became a band, we were basically a bunch of young people living in a squat in West Leeds with some cheap instruments and a desire to have some sort of meaning in the world. But we made a point, right from the very start, of discussing design – labels, logos, on-stage image, all of it. We decided even before our first record release that we would refuse to have a ‘band logo’. That we would change the typeface for every release that we put out. This, we thought, would avoid people painting “our logo” on the backs of their leather jackets. And we stuck to this through the life of the band. No Logos or typefaces that lasted longer than one record release. Keep people guessing.

As a kid, in Burnley, Lancashire, the way things looked was incredibly important. I painted the Roy Lichtenstein ‘Whaam!’ image as a mural on the wall of our youth club. When my friend Tomi got his first motorbike, he asked if I would paint The Stranglers ‘rat’ image on his bike’s petrol tank. I learned that how things look tells us a story of how things are. And from that time on, the look of things was an essential part of the meaning of things.

Which brings us to this book, ‘But’ and how Christian has honoured the spirit of the writing by carefully, craftily, beautifully, doing something with the printed words that elevates and illuminates them. Words in the margins, words that disappear, words that tell stories, words that break free…

I sent Christian the text and basically said, ‘have fun with this’. And he did, even when the fun was painstakingly difficult to create – hours spent aligning the dots on the ‘j’ of ‘joy’ so that they filled in the letters above them. Working out how to send words off a page and reappear somewhere else. Juggling with a blurb that starts on the back cover and carries on into the body of the book. Searching for a typeface created from Mark E Smith’s handwriting.

Playing with typesetting reached a peak in the 1990s when computer-aided design gave everyone the tools to go wild. The result was often an unintelligible mess – a dog’s dinner that broke the rules so hard that it was simply unreadable. What Christian does is always based on his education in setting lead type on a letterpress printer; having a learned respect for text. Knowing both how to construct and deconstruct.

What I’m getting around to saying is that the design echoes the sentiments in the book – it tells its stories but runs off at tangents, it digresses and allows itself to be disrupted. Words suddenly jump out of a page or simply fade away.

When it came to titling the book, I tried insisting to Christian that his name be on the cover. No chance, he said, sucking on a cigarette and grinning. Well, at least have your name on the back? No. On the title page? No. And since it was Christian who was sending the completed manuscript directly to the printer, that’s how we ended up with just the tiniest of mentions in amongst the credits on the copyright page (also, I’ve just discovered, known as a ‘colophon’). Perhaps it’s just as well that Christian doesn’t have any say on the design and printing of this blog.

BUT – A tentative first blog

December 2024

I have a book coming out. You might know that. It’s called ‘BUT’, subtitled ‘Life Isn’t Like That, Is It?’, and I’ve been proof-reading and copy-editing it for months, watching the to- and fro- between the designer Christian Brett and the US publishers PM Press. PM have an editor called Wade who is as meticulous as Christian. They’ve been duelling in a down-and-dirty War of Meticulousness. There are no winners or losers in that battle, just piles of annotated documents and text files and Christian’s madcap, surreal book design sending words leaping from the margins in a bid to escape. The design is sufficiently weird that the printer was quickly coming back with questions like “is p231 supposed to be just a black dot in the middle of a blank page?” “Why are pages 179–183 upside-down?” “The text on the hardback cover is all back-to-front!”

And that’s before we get to what the book is actually about.

The blurb tells me that ‘BUT’ is “a collection of stories about real lives, real people, and real life. Stuttering, wayward, disjointed, funny, ridiculous, and unplanned.” Which is about right. I set off two years ago on a journey to find the people I’d met in my life who had profoundly altered how I thought and what I did next. Disrupters, I called them. I wanted to visit these people who, often unwittingly, had bounced me off in a different direction, I wanted to simply say “thank you.” Some of them were old friends, some complete strangers. And along the way I began to collect stories of disruption, stories that refused to act like the stories we know and love. So the book became a disjointed look at how life isn’t neat and tidy like a film or a play or a novel but is a dislocated series of disruptions.

Remember that old TV series called ‘Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected’? I used to watch it round at my mate Dan’s house, where we laughingly called it ‘Tales of the Well Obvious’, because try as it might it couldn’t avoid being a standard-format TV show with a narrative arc and a satisfying ending. It had a memorable theme tune, though. Bright, ringing arpeggios in a waltz time. I looked the programme up on Google and the first question below the list of websites was: “Who was the lady dancing on Tales of the Unexpected?”. The opening titles featured a naked woman in silhouette dancing a slow and elegant twist in front of a fire, and she was (it says) called Karen Standley, “a secretary and housewife from Berkshire”. I like this digression, aware that Roald Dahl would probably turn in his grave. Or at least twist elegantly. Time for a commercial break.

Skip this ad in 15 seconds –

While I was writing this I remembered that I had to pre-enter a night-time orienteering race that’s happening tonight on the Chevin, a long forested hill above my town. I went on the website and saw that there was just one place left, and realised I’d best register quickly before it reached its limit. I ran upstairs to get my dibber – a small plastic key that you use to record visits to the score of obscure checkpoints – and by the time I bounded down the stairs the race was full. No happy ending to this interlude, just a disappointed sigh and a lonely torchlit run on my own.

Skip

Two disrupters I didn’t put in the book are my children Maisy and Johnny. Children are such a great example of a story without a clear narrative. You never know what’s coming next, do you? I’m telling you this because Johnny (14) just walked in from school with his mate Josh. They share a love of skateboarding but the streets outside are wet, which is a definite no-no for skaters: the moisture gets inside the wheel bearings and wrecks them. Instead both boys tell me how they’ve picked up school detentions by acting silly, and I’m reminded of myself at their age – not a fighter or a geek, just someone who wanted, despite the teachers’ best efforts, to entertain the rest of the class when I should have been learning about Shakespeare’s characterisation of the King of France and how ““the web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together.” To quote comedian Philomena Cunk: “Shakespeare’s ‘All’s Well That Ends Well’ was one of the first-ever examples of the spoiler.”

So here’s a spoiler – accompanied by a slow twist from Karen Standley. It’s the final line of ‘BUT’:

So here we are, I give you: a happy ending.

Almost the end of this blog, too, but not quite. I ventured out onto the Chevin in the dark and had a great run alone in the pouring rain, happy enough not to be racing, and gradually, step-by-step, forgetting the to-do lists and emails to check and songs to work on and blogs to write. Thoughts reduced to a steady focus on the slap-slap-slap of feet on wet soil (that’s a quote from Alan Sillitoe’s ‘Loneliness of a Long-Distance Runner’) and a calm, lonely peace.

BUT is published by PM Press in the USA and UK and is out on February 18th, 2025.

Goodbye To Rod Dixon, Artistic Director of Red Ladder Theatre

(He didn't die, he just left his job)

December 2023

Last weekend, Saturday night in an upstairs bar in city centre Leeds, we waved a big fat partying goodbye to Rod Dixon as Artistic Director of Red Ladder Theatre. You’ll probably know that I’ve been involved with Red Ladder for about the same length of time – I was invited by him to “write something, then” not long after he’d taken the job, we were in an old Victorian pub on the Kirkstall Road and we’d both had a few drinks.

The leaving party went really well and there were lots of references (not least by Rod himself) to his unique style of ‘artistically directing’ – as an anarchic, gobby and often hilarious mixture of crusading politics and fart jokes. But what was missing from the evening was a real sense of what Rod achieved at Red Ladder, behind the silliness and the continued ability to piss people off.

Red Ladder changed direction drastically when Rod took over, shifting from Theatre In Education and community teaching to loud, eclectic shows that could (and did) pop up in black box theatres, music halls, pub backrooms and community centres –often actively seeking out non-theatre-going audiences and making top-quality work on a shoestring of a budget. The budget balancing has been down to Chris, Rod’s long-suffering partner at the helm of Red Ladder. I say long-suffering because it was Chris’s job to keep some semblance of fiscal control over the maddest of ideas, and despite his constant work to get financial backing from assorted ‘partners’ – Unions, theatres, businesses – it was always a struggle with Rod tweeting daily anti-capitalist rants.

Ranting was one of Rod’s special talents. He could rant for Britain. Or rather, for Liverpool, the birthplace he deemed to be a republic independent of the rest of the country. He dismissed (probably unwisely, but you had to admire his front) reviewers and critics, (“If they want to review it, they can get on a train heading north, the pampered bastards!”) blasted the Edinburgh Festival, (“It’s just bloody London on its holidays!”) and of course slagged off London itself incessantly.

Fun as all this was (and I was always laughing along), this all masked an incredible dedication to the craft and art of making populist, daring, clever and important theatre. He and I were big fans of John McGrath’s book ‘A Good Night Out’, which called for theatre to become part of popular class-wide culture and not an expensive pastime for those with money and ‘taste’. The shows he directed were wildly different, stretching from dramas about the bleak, realist, often grim truth of life in marginalised communities to upbeat and colourful musicals with big-name stars. The thing that brought these different forms together was a dedication to radical, hard-hitting politics; a refusal to shy away from pointing the finger at the Westminster Emperors ruining the country. At the same time there would always be a sense of hope and belief in people and in communities.

The fact that Rod could convince actors like Phill Jupitus and Pauline McLynn to head up Red Ladder shows on standard Equity weekly wages (I still remember sitting down with Pauline in a café in Leeds at the very first meeting, where Rod opened up with, “you do know there’s no money in this don’t you?!”) was testament to the belief and enthusiasm he could generate. He was a firebrand, a clown, an agitator, a dynamo and a naughty boy (!) – but above all a really, really good director and inspirer of people.

Red Ladder will get a new Artistic Director and I don’t doubt they’ll be brilliant. And they’ll be starting from a place – a respected and ‘punching above their weight’ place – that Rod and Chris have created and built over the years of their partnership, on next to no money, a place where the important stuff is part of every production, every workshop.

I can’t believe Rod is disappearing to live on a smallholding in Scotland. It just doesn’t seem feasible. No smallholding can contain that level of energy. But I’m dying to see how it works out, and I wish Rod and Ella all the best, and before they disappear I just wanted to write this stuff down in case anyone should forget how much our tiny bit of the world has been re-shaped by the passion and heart of this man. And so to finish, in honour of Rod, here’s a joke:

A theatre director was worried that his leading actor hadn't turned up for the opening performance. His assistant came up to him.

"Sir, you just received this letter from the leading actor."

The director took the letter and read it.

"Dear sir, I am afraid I cannot come in for the show tonight as I have..."

The director stopped reading and kept staring at the letter.

"I can't read his writing, is that an I or an O?"

The assistant looked at the letter.

"It's an I"

"Thank goodness, I thought he'd shot himself"

Barry Coope – Only Remembered

A brief tribute to one of folk's finest voices

In 2002 Chumbawamba wanted to create an album of songs – Readymades – based on samples of various English folk artists, so we needed permission, of course, from the artists themselves. Three of the samples we’d used were by Coope, Boyes & Simpson, simply because we loved them. We loved their voices, their harmonies, their words and their ideas. We wrote to them to ask for permission and they wrote back to say, simply, ‘use our stuff, gladly!’ No mention of royalties or legalities.

I knew Jim Boyes from his singing with Swan Arcade in the 1980s. Me and Lou, in the early days of Chumbas, had travelled across to Holmfirth to see Swan Arcade, three incredible voices that could fill any room. We’d always sung acapella songs even as a noisy punk band, so Swan Arcade were simply inspirational. Skip on a decade and here was Jim Boyes now joined by Barry Coope and Lester Simpson, the three of them taking the power of Swan Arcade and adding astute, clever songwriting. Three male voices pulling together, stretching the limits of acapella singing, stepping outside tradition. There were times when you’d see and hear them singing together and marvel at the way the buzz and tone and burr of these three voices could make such a solid, perfect, generous sound.

Some time during the recording of that Readymades album we trooped across the Pennines to Oldham to see them perform and introduced ourselves, straight away becoming friends and discovering that they were genuinely lovely blokes. Before long we became part of the No Masters Co-operative, a collection of northern English singers and songwriters collectively and independently putting out records; Coope, Boyes & Simpson were the collective’s mainstay, its spine. We would gather at each others’ houses every few months to sit round a big table eating biscuits, drinking tea and putting the world to rights; we shared stages at festivals and sang on each others’ records.

Barry was always there at the meetings, a friendly, engaged and active member of the co-op, ever-helpful and good humoured. No matter how many stages we shared – Barry was there singing with us when we played our last concert in Leeds – I couldn’t get over that voice, the one that starts the Coope, Boyes & Simpson song ‘Jerusalem Revisited’ – that powerful, plaintive cry of “Out there on a doomed estate, a house is burning down…” Simply perfect.

The last time we sang with Barry, Lester, and Jim was onstage at their final gig, at the Derby Folk Festival in 2017. We joined them for three songs, finishing with ‘Only Remembered’ – as I’ve got older I cry easily, so I can well remember that last farewell chorus, holding a lyric sheet and holding back the tears, singing along with the wonderful sound those three made together.

Fading away like the stars in the morning

Losing their light in the glorious sun

Thus would we pass from this earth and its toiling

Only remembered for what we have done

Only remembered, only remembered –

Only remembered for what we have done

Shall we at last be united in glory

Only remembered for what we have done

Crass, Commoners Choir and Growing Old Disgracefully

June 2021

I first came across Crass as a teenager in Burnley. It must have been about 1978, though the accelerated years between ’77 and ‘82, even at the time, seemed to pass in a frenetic blur. Gary Brown, bassist with local punk legends Notsensibles, brought their record into Mid Pennine Arts, a grand and tatty Victorian building that all the punks frequently took over as we put together our various fanzines and posters for gigs. I’d become mildly interested in anarchism and was fascinated by Crass’s artwork – stark, monochrome, stencilled lettering alongside incredibly detailed soft pencil drawings of dystopian scenes.

The music was as strange a combination as the sleeve; at first listen an almost unintelligible volley of barked words over a biting metallic roar, but then a realisation of the clever and unusual arrangement – drums driven by military snare rolls and off-beat cymbal crashes, two guitars split either side of stereo sounding as if they were played through transistor radios, and a rolling, melodic bass that somehow brought tunefulness to the clattering whole.

The vocals were equally unusual – male and female, sometimes shouted and screamed, sometimes whispered poetically, sometimes with operatic whoops and yodels. That first record was a strange thing indeed, and unforgettable.

When I was 18 I went to Maidstone Art College in Kent, thinking it was close enough to London to allow me to easily get to the capital’s punk gigs (I was wrong, the last train back to Maidstone was about 9 o’clock). Somewhere in the three months I stayed there, in between being chased up the high street by mods and threatened by teddy boys in a toilet, I caught a train to some unmemorable Kent village where Crass were playing in the local scout hall.

What I saw of Crass there was pure theatre – the lighting (all from below), the clothes (all black) the pre-show routine (mingling with fans outside and handing out stencil-copied leaflets on anarchism), the post-show routine (finishing the cacophonous set and immediately stepping off the front of the stage to drink tea with a bewildered audience) and the stage setting (beautifully designed banners hung across the walls) – all of it creating a sort of travelling circus of ideas, art, anger, shock, community and confrontation.

It was only later that I discovered Crass had roots in experimental performance art, and were part of a fascinating tradition of eccentric British art school mavericks. Back then, walking home umpteen miles back to my digs in Maidstone, I understood only that this band were here to shake me up, to make me think, to challenge what I thought I knew about rock ‘n’ roll, politics and the world.

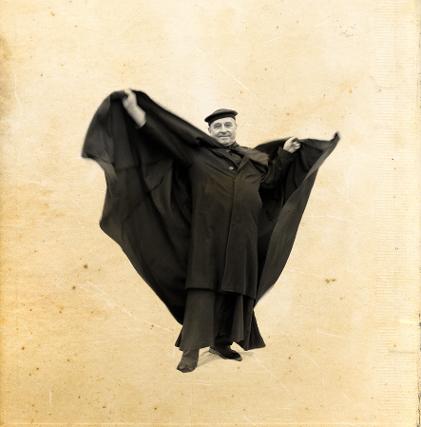

I travelled around the country for a short while, catching them at gigs in various towns and cities across Britain, watching this weird and compelling jumble of politics and art. At several of these gigs there’d be an older man called Raymond, perhaps in his late fifties or early sixties, wearing a black beret and black overcoat. He smiled a lot and spoke in a soft eastern European accent. Later I got to know him, but at the time I remember thinking – that’s what I want to be like when I’m sixty. I don’t want to be watching telly in a favourite armchair, retired from some job I had for a lifetime. I want to be travelling around the country, following the most interesting noise, looking interesting, growing old disgracefully.

That was all over 40 years ago now, 40 years to draw a huge, higgledy-piggledy circle that goes from first hearing that Crass record to a faceless room in Leeds where I’d put out a call to see if anyone was interested in being part of a choir that would “mix the choral power of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir with the astute punk dynamism of Crass”. Around twenty people gathered in that room and together we decided the idea could work. We would call ourselves Commoners Choir, wear all black, sing about putting Boris Johnson’s head on a stick (this before he was even our Foreign Minister) and sing on top of mountains, on boats, in churches… and the choir grew, and now stands at well over a hundred members.

Sometime last year I heard about the ‘Crass Remix’ project and just felt that, well, the ‘fit’ was too perfect to miss. The invitation from Crass was to experiment with the mix, and we decided that turning G’s Song – a hurtling, full-throttle 37 second blast – into something choral and hauntingly melodic would echo the band’s strangeness, that challenging of preconceptions that had always appealed to me in the first place.

G’s Song ends with the line ‘… and they’ve got no problem when you’re underground!’ which can be taken in two ways. Either it’s a gloomy fatalism that says we’re no trouble to the establishment/the system when we’re dead – or it’s a declaration of intent that we need to stop being politically underground and take our ideas into the world. I prefer the latter, obviously.

When I became interested in anarchism as a teenager I went to an evening meeting of the anarchist Direct Action Movement in a tiny café in Burnley. Compared to the theatrical shock of Crass, it seemed so dry and lifeless and, above all, hidden. Crass took their political anger and put it into popular culture, from record decks and the backs of jackets to courtrooms and teen magazines and questions in Parliament. So much of popular culture is now online, and during this last year of lockdowns and enforced hibernation, that’s where Commoners Choir have been getting out into the world – what we’ve proved with our choir of misfits and ne’er-do-wells is that even without gathering in public spaces and singing, even without playing concerts, we can make songs and films and zines and get stuff out into the world. Avoiding the underground. The Crass/Commoners Choir remix leaves that final line – they’ve got no problem when you’re underground – to Steve Ignorant’s original strangled vocal. It’s a call to arms.

The Commoners Choir/Crass Remix will be out in early August, accompanied by a film we’re in the process of making. For me the remix is a good marker of time and ideas, and a confirmation of how the best art can change our lives. Among the massed ranks of Commoners Choir there are quite a few whose lives as teenagers were impacted not just by Crass but by punk’s call for challenge, change and social justice; this remix is one way of connecting these threads of a lifetime (and having a ton of fun doing it).

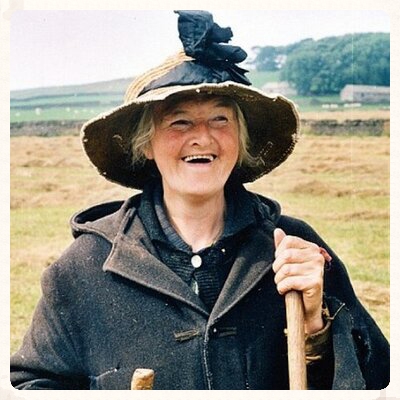

In our house we have a huge photograph of Raymond, the old Crass fan, up on the wall in our kitchen. He died about twenty years ago, but he’s there with a big smile on his face, wearing a long black cape and his trademark beret. I can’t look at it without smiling. Actually I can’t even think about it without smiling. Raymond, soundtracked by Crass’s intense and clever version of punk, became a symbol of a life well spent, a life full of adventures and ideas, where, somewhere down the line, a choir’s four-part harmonies and a punk band’s rhythmic aggression might somehow find a way to work together.

Out on One Little Independent records, Friday 6th August – 12" Single Physical + Digital Release Focus Track: 'G's song (Commoners Choir Remix)'

All Or Nothing At All – Me, Billy and Steve

August 2020

Well, here’s an interesting one... If you’re at all interested in running. Or nature. Or the history and culture of sport. Or about how, quite a few years ago, I spent 23 hours running around a high-level ribbon of Lakeland peaks and met a man who I think we can safely describe as a ‘legend’. That was Billy Bland, and his story has just been written and published by writer Steve Chilton – which is where this blog becomes something other than one of my normal run-of-the-hill blogs.

This is a guest blog from Steve, who has just written ‘All or Nothing at All’ about Billy Bland, published on 20 August 2020. The blog is part of a Blog Tour to celebrate the book’s publication. What this means is that since Steve can’t go round bookshops signing books, he’s piggy-backing onto various people’s blogs, interviewing the writers about their connection to Billy and to the wider social context of fell running.

For context: the Bob Graham Round, which features heavily in our discussion, is a run which takes in 42 of the highest Lake District peaks (28,000 feet of climb), is 66 miles long and has to be completed in under 24 hours – Billy Bland completed it in around slightly under 14 hours.

Right then, take it away, Steve...

The following is an edited extract from a recent interview between the author and Boff Whalley. In it they discuss Boff getting into fell running, discovering the Bob Graham Round (BGR), and how he suddenly had Billy Bland pacing him on the last leg of his own round because one of his designated pacers had to drop out at the last minute.

SC: When and how did you become aware of the BGR?

BW: When I first got into fell running I was captivated by the culture of the sport, and the history and the mythologies. Reading Bill Smith's Stud Marks on the Summits - the first 100 pages about open fell running, about village fell running, naked fell running, and racing up and down mountains, to win a prize pig or whatever - it fascinated me. Fred Reeves and all the 1950s and 1960s era stuff, I just loved all that. It felt like a sport that wasn't just about excellence in athletics. It was about culture and community and all those things which I love anyway.

SC: When did you discover the fells?

BW: It was 1988 I started running in the fells. That was an interesting era because there were three things happening basically, and I hadn't kind of realised how big they were until recently. Firstly, women were being recognised properly in the sport, being allowed to run in the long races and that sort of thing. There was a lot of stuff to do with the environment, people were waking up to the idea, especially after BNFL sponsored the 1988 World Cup (in Keswick), and it caused loads of controversy on the pages of The Fellrunner. Then there was the whole amateur versus professional thing, which was really big. All those things meant fell running had a connection with the world. I find that all fascinating.

SC: How soon did the fact that Billy Bland had done this amazing thing in 1982 (his 13-53 BGR record) get on your radar?

BW: I soon became aware that some of near legendary fell runners were still racing. So, people like Andy Styan and Billy Bland were two kind of heroes, because I always loved descending. I loved rough descents and mad descents. To see those two competing and still running really fast was just fantastic. I then found out all about the Bob Graham. I remember the little pamphlet with a picture of Bob on the front with his big billowy shirt. I thought this is great, this is the kind of sport I love. It an amazing history of it and such a great thing to do. I thought, if I am going to do one thing while I am running it will be that.

SC: How soon into your running time did it become a possibility that you'd do it then?

BW: Nobody at Pudsey and Bramley (my club) was interested. They weren't doing mountain marathons and that. Maybe one or two people here and there, but in general it wasn't a club that did that. We were a club that raced championship races, and was more like a gang than a club. The idea of planning for a BGR and spending six months doing long runs and that sort of thing wasn't part of what we did. We did hill reps and we did track sessions and everyone went to the same races together. Pudsey and Bramley had a reputation for short sharp races with good downhills like Burnsall, partly thanks to Pete Watson really. Then well into the 1990s I thought I might have a go at the BGR. I remember asking around at Pudsey and Bramley to see if anyone was interested, and no-one was. So, I became the first person at the club to do it, which is bizarre really. Then years later a big bunch of them did it, because I kind of convinced everyone that it was a brilliant day out. Then 5 or 6 of the did it at once.

SC: Did this mean you had a problem finding pacers for yours?

BW: Yes, definitely. I was doing it with people from other clubs, recce-ing and stuff like that.

I did a lot of recce-ing with Geoff Read from Rochdale, because he had done it previously. I didn't know many people that had done it really. I wasn't part of that scene at all.

SC: How did networking work, pre-social media?

BW: Talking after races usually. I got some people to run it so that I had someone with me. I said, I have recced it all, you don't have to do anything, just be with me. No nav required, so it wasn't like it was supported in that sense.

SC: Is that because you wanted to be in the BG Club, that you wanted someone with you at all times?

BW: Yes, I did.

SC: Knowing your attitude and personality I thought you might have just gone round the route and said ‘sod the club, I am not really that bothered’?

BW: Yeh. I can understand you saying that, but I love the cultural tradition of honouring these amazing people that did it in the past and set it up, and thinking I want to respect that. I am not against organisations and people, and things like that. But having said that, if people do want to get up and go and run round it as fast as they can on their own, then that is fine.

SC: The club was setup to acknowledge the history, like you say.

BW: When I decided I wasn't ever going to run a road marathon again it wouldn't stop me from going and running 26.2 miles on me own round the woods and trails. Some of the races that are organised - you could just go and run round them, like Ennerdale or whatever, any day you wanted. But to be part of that race is having Joss Naylor running in it or setting it off, and understanding what it meant to people to run that race in the past, I just think ‘No, it is great to be part of the tradition’, which the race is. I like that. It is the same with the BGR. I kind of liked the fact that others in Pudsey and Bramley hadn't done it too.

SC: You mentioned trying to get Gary Devine interested, did you ever succeed?

BW: No. Not at all. But, he was the reason I ended up running with Billy though. Gary had no recce knowledge but he was going to support me. He just said he'd come with me on one of the toughest legs, and it was a leg that he’d be good on, since he’s such a good mountain runner.

Then the week beforehand, he was ill and he couldn't get out of bed, but he offered to help find some people to do it with me. At that time I had people for some of the legs, Geoff Read and Fred Deegan, really good runners and navigators. But no-one for the last two legs, which was worrying, but Gary just said, don't worry, with a wink. We both knew Scoffer (Schofield) so we got in touch with him. And he turned up with Phil Davies. It was like two of the best Lakeland mountain runners setting off with me from Wasdale on leg 4. They were great and knew all the secret Borrowdale club paths! Danbert (from the band) did leg 2, I think. He might as well have been running on the moon, he had no idea where he was, but he’s always good company.

SC: You said there was no particular time expectation?

BW: It was a day out. I knew I wanted to get it in under 24 hours. I aimed for that and I didn't push it at all. That wasn't my kind of thing. The races I did well in were all fairly short races. I knew I wasn't going to break Billy's time!

SC: You pull in to Honister at the end of leg 4. Did you know by then who the next pacers were going to be?

BW: Yeh. My brother-in-law Mark was going to run in with me. That’s all I knew. He didn't know where he was going and he hadn't done a lot of running either, but that was fine. I knew he was going to be there, but the fact that Billy and Gavin Bland were there was just hilarious. Gary had drafted them in, I was really shocked. In a way I felt a bit sorry for them! I knew Gavin a bit before and I had spoken to them both before, but didn't really know them. What a good spirited thing they did for me. Incredible. Mark (my brother in law) was gobsmacked – “Are they gonna run with you?!” he says. All those Borrowdale runners have such a good attitude to the sport. To turn out like that and help someone on a BGR is just great. If there are people running in my neck of the woods who ask for help I would say 'yeh, I'll come out'. It’s the spirit of the thing. I still don’t know if I ever thanked all those Borrowdale runners enough.

SC: That is the ethos of the Rounds, isn’t it?

BW: It is interesting as well, because my attitude to Kilian breaking Billy's record is that it is absolutely fantastic and a great athletic feat. But, it will never match what Billy did, not in a million years. As you know, like with the rivalry between John Wild and Kenny Stuart, those were times when people didn't have a full support crew around them like the culture of professionalised running now. These recent feats are amazing but somehow don't match the idea of someone that is rounding up sheep all day and then saying right I'll have a crack at the BG tomorrow! It is a different world. It is hard to talk about these things without sounding like an old curmudgeon, but it is the same with digital technology – It is fantastic, but at the same time I prefer the authentic experiences that came before everything was online.

SC: You were navigating yourself, did you ever think of doing a solo or unsupported round?

BW: I think the only reason I probably didn't was that I thought no-one will believe me. I think nowadays you would always believe someone because there is usually an army of people at each road crossing and people are out there spotting people doing these kind of challenges. But at Pudsey & Bramley no-one was really bothered about what I was doing. If I had said, ‘oh I have just done the Bob Graham this weekend’, they would have said, ‘alright what’s that’. I needed it validated. ‘No I honestly went to every peak!’ But if I did it now, I DEFINATELY wouldn't do it with a tracker so people could dot watch.

SC: why so adamant?

BW: I am doing a theatre show about running with a friend of mine, Dan Bye, but it has been put off till next year. Part of it involved an 85 mile run which we were both going to do from Lancaster down to Kinder Scout. It is to do with land rights and land ownership. But I couldn't do it because I broke my toe, so I supported him. He had a digital tracker which was the first time I have had to deal with that kind of thing. I was on road support watching this little digital dot moving along. I found it really frustrating because three or four times it stopped because it lost GPS signal, a couple of in the night-time. You are completely lost, you just think this is ridiculous. If it wasn't for this technology you'd do it all different. You would have more safety times measures in for a start. Seeing a dot – you think ‘oh yeah all is fine’.

SC: What are you thoughts on access to land, and the dichotomy of access against erosion?

BW: I do think that there comes a point when I would look at the Bob Graham and think I am not going to do that as it has turned into a motorway. When I first did the Three Peaks race in about 1989 they had just paved and duckboarded two really big sections of it. It was really boggy coming off Pen y Gent. They changed the route slightly and boarded it. Even then I thought I am never going to do this race again, it is just making it kind of too easy. If the Bob Graham gets like that then I think people need to have a think about running somewhere else. You go into the Howgills which is just 30 mins drive away and there is nobody there. You can run every day and not see any runners at all. There are always other places to go. I think runners are a bit more sensitive to environmental stuff than a lot of other people.

SC: in book I detail Kilian Jornet meeting Billy Bland, and being encouraged by him at road points

BW: Yeh. I think Billy turning up and being supportive of it all made such a difference. And I think Kilian’s run was amazing.

SC: I also quote Billy saying to Kilian that he stopped for 20 mins in total on his round and he had to beat the time by more than those 20 mins.

BW: That is funny. I remember somebody saying to me that if you stop on every summit just for a minute and catch your breath and have a look around you have lost a lot of time, so don't stop.

Yes indeed – 'Don't stop'.

‘All or Nothing at All’ will be published on Thursday 20th August and can be obtained from all good bookshops and online at Amazon.

Live book launch, Thu 20 Aug 6-30pm:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVbuEUURETE&feature=youtu.be

About the book:

All or Nothing at All: the life of Billy Bland. Sandstone Press. Format: Hardback. ISBN: 9781913207229. Publication Date: 20/08/2020 RRP: £19.99

All or Nothing At All is the life story of Billy Bland, fellrunner extraordinaire and holder of many records including that of the Bob Graham Round until it was broken by the foreword author of this book, Kilian Jornet. It is also the story of Borrowdale in the English Lake District, describing its people, their character and their lifestyle, into which fellrunning is unmistakably woven.

About the author

Steve Chilton is a runner and coach with considerable experience of fell running. He is a long-time member of the Fell Runners Association (FRA). He formerly worked at Middlesex University as Lead Academic Developer. He has written three other books: It’s a Hill, Get Over It; The Round: In Bob Graham’s footsteps; and Running Hard: the story of a rivalry. He has written articles for The Fellrunner, Compass Sport, Like the Wind and Cumbria magazines.

He blogs at: https://itsahill.wordpress.com/

Growing Up With Neil

31 January, 2019

We all have heroes, don’t we? Even as an avowed anarchist (No gods! No masters!) I have people I’ve idolised and looked up to. Heroes are superhuman, out of reach, better than us. We aspire to be them but know we never will be. Bowie was a hero. Johnny Rotten was a hero.

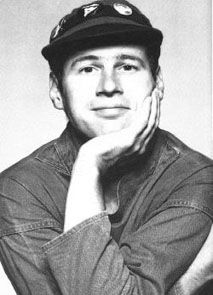

Neil Innes, with that plastic duck on his head and a reputation for being a lovely bloke, wasn’t a hero for me. He was more than that – better than that – he was someone who taught me what I could be; as I grew up he became a practical, down-to-earth and workable model. That’s more than a hero, isn’t it?

Neil Innes died yesterday, and I feel like I lost someone who’s been around me my whole life. He was there when I most needed him to be there; when I decided as a 15 year-old I wanted to go to art school and, on a collection of cassettes, when I dropped out of college to be in a band. It’ll be strange not having him around.

Some time in the mid 1970s I was round at my mate Mick Binns’ house, skiving off school, obsessed with Monty Python and pop music. Me, Mick and our friend Stanny wanted to form a band but none of us could play an instrument. Instead we decided to make our own comedy shows, writing and performing sketches and recording them on cassettes. Mick had an older brother and so had access to records that we didn’t know about – I remember being impressed that he had the first Sparks LP, but being nonplussed hearing early Bruce Springsteen. One afternoon he declared that he’d borrowed an LP called ‘The Doughnut In Granny’s Greenhouse’ by an old 1960s band called the Bonzo Dog Band. The preposterousness of the title and the sleeve photographs of the band registered it as fascinating enough for me to ask to borrow it. Two weeks later I was buying the album for myself in a record shop in Rawtenstall, Lancashire, convinced I’d found the meaning of life.

The make-up of the Bonzos was important. They were a bunch of maverick artists whose various contributions made the band eclectic and compelling. Most of the focus was on Viv Stanshall, an eccentric genius and incredible wordsmith. But I gradually came to realise that there was a quieter, but no less important, voice in the band.

And I grew up with that quieter voice. It gave me hope.

I don’t want to write an obituary, much as they’re essential and beautiful – I don’t want to write one of those pieces you read in the papers. How such-and-such was brilliant at this and that, how lovely they were, how they changed the world. I want to write about how this quieter voice impacted me in such a way as to effectively give me a blueprint for getting through life.

I was never going to be a Viv Stanshall. He was obviously an outrageous and incredible personality, one of a kind, a born poet and performer. But he needed a Neil Innes. I have a Bonzos bootleg of the band rehearsing, and there’s a point where the band are trying a new song out – they launch into it and Viv comes in on the wrong beat, throwing everyone out. The song stutters to a halt. Neil at the piano gently instructs Viv to count the bars to the intro before he comes in, half-encouraging, half-tired of having to deal with Viv’s alcoholic waywardness. They set off again and click, and all’s well.

And that was Neil’s job for a while. Looking after the frontman, making sure it could all be held together. All the while, he was contributing his own beautiful songs, rarely stepping out front (despite his song ‘Urban Spaceman’ being the group’s only hit) but always ensuring the band held tight and kept time.

So, suddenly in love with this new and unsung musician, at school I covered my books with a photocopied photo of Neil wearing a dress. I presume (looking back) that I just loved that he looked beautiful and weird at the same time. I then went out scouring the record shops in Manchester finding Neil’s more obscure albums (Grimms, The World, etc), taped all his TV shows on a portable cassette recorder, and eventually saw him live at some awful student ball in a London art college.

And when I started to be in bands myself, I realised that Neil was a role model for what I wanted to be – essential to the band but not at the front. The first band I played in was called Chimp Eats Banana and we formed without any of us knowing how to play an instrument. That didn’t matter – I’d grown up on the Bonzos, so I knew it was all about theatre, humour and shock. I stayed at the back, strumming an electric guitar I’d bought on Maidstone market for £10.

I followed Neil through the Eric Idle / Rutles years, regularly seeing him play in various arts centres and theatres, and eventually, twenty years later, I met up with him to do an interview after a show at Leeds City Varieties. Knowing I couldn’t ever explain just what his example had meant to me, we had a very pleasant chat; and he at least proved that he was indeed the bloke I’d always imagined he’d be (friendly, unassuming, humble, generous, clever).

I think I have everything Neil ever recorded. Bits of it are awful – that pro-monarchy Silver Jubilee single he released in 1977, just as I was being enthralled by punk, too often comes to mind – but overall it’s a lifetime of ideas that could fill up... well, that could fill up my record collection. Across all those recordings there’s no fixed genre, no fixed style, nothing other than ideas. Ideas of where to go to next. That, to me, is one of the things that makes a great artist. Flitting around, not doing what you’re expected to do.

The other day I was thinking about lyrics, about great song lyrics. And I thought, there are two lyrical snippets that just amuse and amaze me whenever I think of them. And they were both Neil’s. Both are based on rhymes.

“You’re so pusillanimous, oh yeah –

Nature’s calling and I must go there...”

“Hey you, you’re such a pedant!

You’ve got as much brain as a dead ant!”

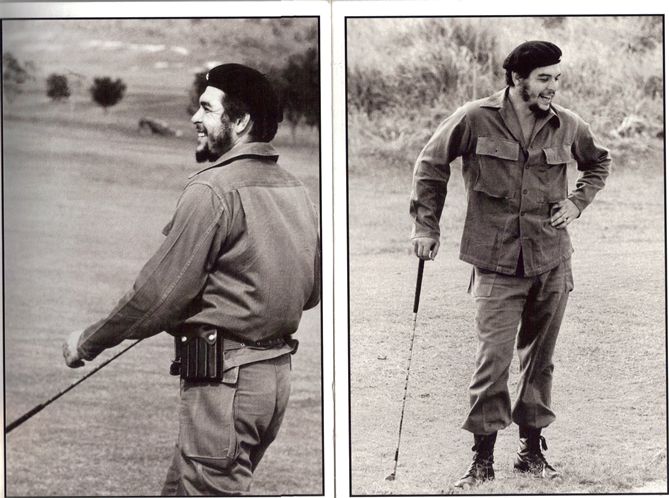

So anyway, Neil wasn’t a hero. Not like John Lennon or Emma Goldman or Che Guevara or whoever. He was more than that – he was someone who made me think, “that’s how I can navigate my way through life. Through art. Through music.” In my obscure little corner of popular culture, I could never have been Viv Stanshall. But Neil Innes, he was my man. And always will be.

Ping-Pong At The Opera

30 September, 2019

“I’m just thinking about my family now.”

I’ve been off-handedly critical of opera for the last decade or so, for no other reason than that it gets a disproportionately large slice of arts funding, possibly due to its ‘high art’ connections to the social life of this country’s millionaire club. In my home city of Leeds, Opera North (at the last round of Arts Council funding) received over £40 million – almost half of the city’s entire arts fund allocation. This is just NOT FAIR.

It doesn’t mean I hate opera. Opera North are an innovative and creative organisation and I can’t blame them for mopping up the arts budgets. But it means I have an in-built distrust of opera, along with a class-based prejudice (dinner jackets and shiny shoes!) and a scary memory of my mum listening to a 7” vinyl single of tenor Jussi Bjorling singing the hell out of Bizet.

Anyway, about a year ago writer Sarah Woods invited me to be part of a project with Welsh National Opera in Cardiff, working on a piece of music about refugees and asylum seekers. Obviously I jumped at the chance. Whatever my views on opera, here was an opportunity to both get out of my musical comfort zone and properly engage with all the personal and poltitical issues surrounding immigration. I mean, standing back from it, wasn’t this a case of two worlds diametrically opposite? The gratuitously-monied arts and the under-funded plight of displaced families? Let battle commence.

Sarah is brilliant. She’s better at dealing with people than I am – we’re both from similar punk/squatting backgrounds, but possibly because of her London metropolitanism, she can walk into a roomful of strangers with confidence and ease. She maybe doesn’t have as big a chip on her shoulder; whatever it is, it works – she can shift between the two worlds (opera house and refugee centre) easily enough to make this all possible.

What we wanted was to make a piece of music that used the words of refugees and asylum seekers to tell a story of hope. We had a title – ‘Hope Has Wings’ – but that’s all. We’d be working with the clients of the Oasis refugee centre in Cardiff (‘clients’ is the word used for the centre’s users). It’s an amazing place that’s grown within the empty shell of an old church in urban Cardiff to become a lively, central gathering place for the city’s huge influx of refugees. Some of the clients tell stories of arriving in Dover, being put on a bus by immigration officials, and finding themselves in Cardiff. Lost, alone, alienated, bewildered. The Oasis Centre is a lifeline. When I first visited I was amazed by the hubbub of different languages, the smell of the day’s cooked lunch, the to and fro of everyday life. There was a barbershop in the main hall beside the ping-pong tables. A class teaching English each morning in a room where the cupboards are full of percussion instruments. There’s legal advice, washing facilities and places to relax. Music groups, mother-and-baby classes, arts and crafts, cookery, a creche, writing courses.

Right from the start we agreed that this thing we were here to create should be performed not to an invited audience in the WNO halls at the Cardiff Millennium Centre but right here at Oasis, to an audience including the refugees.

We held weekly workshops. The thing with people who have refugeee status is that they have no routine. They are constantly moving, constantly at the beck and call of interviews, tribunals, appointments, hearings; consequently each workshop we held would often have a different set of people. We encouraged them to share their ideas of hope, and avoided prompting them to share harrowing stories of their journeys from war-ravaged homelands and their separation from parents and children. Nonetheless, over the few months we worked there, these stories inevitably surfaced. People who had been teachers and doctors in their home countries talked of being unable to work in Cardiff, told us about their children they hadn’t seen for a year or more. Fortunately, through all the workshops and discussions and wonderings and wanderings, we had the help of Oasis worker Lydia, whose youthful energy held all the madness together – Lydia knew every client by name, and knew their stories.

Meanwhile, I was dealing with the much more banal and petty problem of writing for opera – utterly (and wonderfully) out of my depth, wrestling with writing a score for a string quartet and twelve operatic voices. Sarah’s lyrics, cleverly crafted from the words she collected in the workshops, were easily translated into little singalong pieces with guitar. We’d take these along to each Oasis workshop and everyone would sing a reflection of what had been written the previous week. But how to translate this to a performance by the Welsh National Opera?

I both loved and feared the challenge, and relished the feeling of wading too far out beyond the shallows. I asked that we have an Arabic percussionist, preferably one of Oasis Centre’s clients. And I wanted the whole thing built around a classical guitar playing simple arpeggios – no piano. The producers at WNO raised their eyebrows but said yes, sure. I had no idea what I was doing, but believe me it was strange and unpredictable FUN. Like punk, like starting a band in 1978 – not sure what was coming next, eagerly looking around the next bend.

The refugees’ words made it work. Sarah created a moving and beautiful narrative from their talking and from pencilled words on scraps of paper that moved through different stages of hope, from desire to despair, from faith to action, and finally to a sense of a shared, hopeful future. It was these ideas that we took into the WNO’s rehearsal rooms just three days before the performance.

The WNO is housed in the Millenium Centre, that huge building in Cardiff with the big words on the front. Looking up at the building during a break from rehearsal I took a photograph of the one word: ‘Sing’. Inside it’s a rabbit-warren of corridors and swing doors. You can follow your nose in there and never come out again. The rehearsal room we would be working in, when I found it, was an aircraft hanger of a place, with three (yes, three) Steinway pianos and an army of invisible people who set up the stools and music stands before you arrive. This is where the money goes. This is the arts funding, right here in this enormous room. And I’m part of it.

What drives this project though isn’t some abstract idea of huge and impressive musicality but the down-to-earth stories of 30 or 40 refugees. The re-telling of stories, the chance to give voice to people who are, essentially, voiceless. We hoped that by taking this performance into the Oasis Centre we could somehow, in a small way, share out – across the city – the connection between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

There are twelve opera singers. They’re in groups of three, ranging from Bass to Soprano. During the first rehearsal I realised that with my choir head on I hadn’t realised that these singers – these amazing singers! – don’t need to be grouped in threes; one of each would have done the job perfectly. Then again, me and Sarah had written two parts of the piece which used all twelve voices to sing, shout and converse in different languages, so I didn’t need to feel too guilty about waste. And besides, the twelve singers were a delight to work with (and I think they loved the chance to break free from musical convention in order to yell and blurt). So, too, was everyone else we worked with at WNO, from the directors and producers to the engineers and translators. No Jussi Bjorling and not a shiny shoe to be seen.

So it came to the performance. The setting was an evening dinner at the Oasis Centre. Every week there’s a special meal prepared by chefs from different parts of the world – people who worked as chefs in their homelands who can bring their incredible skills to a disused church in south Wales. This week there’s a special menu to complement the brilliant hand-picked string players and singers from the WNO. A three-course meal with a musical re-telling of the clients’ stories of hope, of the future.

By now I can see what I did wrong, how I misjudged the vocal ranges of the singers, how I limited myself to tempos and keys in order to keep it all simple. I could have been braver. But watching and hearing the opera singers singing those words, which Sarah had picked out from those weekly sessions in the creche at the old church, I realised how important it was to be part of telling those stories, and how satisfying it had been to work on the project.

There was one small part of the twenty-odd minute piece that always ‘got’ me. At one of the last sessions with the clients at Oasis, we’d asked the assembled group to write down simply what they were thinking about, after we’d had a conversation about hope. Just a few words, write them down, fold up the paper, pass it to Sarah. She shared some of them with me after everyone had gone and one in particular stuck out: it simply said,

“I’m just thinking about my family now.”

Thinking of a family thousand of miles away. A family cut off and distant.

Sarah wrote it into the performance, as part of a spoken word section. During rehearsal, whenever the singer spoke those words, I would find myself almost crying. The same in the actual performance at Oasis. Even writing this, it makes me want to cry. I’m a songwriter, I write music, I write people’s stories. But that sentence – forget my prejudice against opera, my worries about musicality, my comfort zones, whatever – that sentence is why I do this stuff. We’re living in a world that will deny the right of people to be with their families, and that denial is based on economics and ideology. Not on humanity.

Right now Sarah and me are cooking up another project linking the clients at Oasis with Welsh National Opera, which we’ll start on later this year. Next year will mark WNO’s 75th anniversary – it was created in 1945 – and it seems fitting to make the piece around the notion of the Welfare State with all its connections to social justice, empathy and care. So it’s back to the frequent trips to Cardiff and the Oasis Centre and the three Steinways and wondering how it’ll all turn out; knowing, all the while, that at the end of a two-day workshop or rehearsal session I can get back to my family – more aware than ever of how, in this chaotic messy age, that can somehow be a privilege, not a right.

Opera singing at Oasis Centre. Photograph by Tess Seymour

Tyranny With A Mandate

30 August, 2019

“Democracy! Bah! When I hear that word I reach for my feather boa!”

(Allen Ginsberg)

I think my first taste of how British democracy works was watching how the Labour Party hounded, bad-mouthed and expelled its left-wing members around the time of the 1984 Miners’ Strike. I was new to politics, but already learning to be cynical from seeing how powerful men in cigarette-stained committee rooms gathered to draw up new rules and regulations (all seemingly accompanied by that miraculous word ‘mandate’) which would shore up the power around them and rid their own body politik of dissenters and radicals.

Tomorrow there’s a protest against De Pfeffel Johnson’s ridiculous coup-lite. His ham-fisted manipulation of constitutional protocol is so blatantly and outrageously unfair; the man is a revolting, power-hungry, old-school racist toff. Nevertheless, my marching, demonstrating, singing or writing won’t be ‘in Defence of Democracy’. By which I mean, British democracy as it stands. What the Tories are doing, as they so smugly know, is perfectly legal and within the country’s constitutional framework. It’s democratic. They’re not stupid. They understand how to manipulate democracy and always have done. Manipulate it by controlling press, TV and radio (and, it transpires, the internet and social media). Manipulate it by ensuring a steady flow of public school and Oxbridge MPs into both houses of Parliament, judiciary and corporations. Manipulate it with gerrymandering, nepotism, cronyism, and the simple weight of ‘majority rule’(even when you have to pay £1 billion to bribe another party to ensure such a majority): all of it falls within the framework of British democracy.

“Democracy is a system that gives people a chance to elect rascals of their own choice.”

(Doug Larson)

We have this idea that dictatorships arise from nowhere, armed generals staging palace coups, that sort of thing. But sometimes they emerge, slowly, from democracies facing economic or polititcal crises. When I say emerge, I mean they are voted in, by electorates sick of poverty and alienation and swayed by streams of propaganda. The word democracy comes from the original Greek word meaning ‘rule by people’. It’s an admirable idea, obviously, but it can only exist while the people – the electorate – have equal access to knowledge, equal understanding of what they’re voting for. A recent report showed that just three companies, run by a trio of old school viscounts and billionaires, own 83% of the British national print and online newspaper market.

“Four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than a thousand bayonets...”

(Napoleon Bonaparte)

Despite the inherently unequal access to information and to opportunity, British democracy has served many ordinary people well down the years. We’ve used its basic idea as a way of building on progressive, communal, inclusive ways of changing society. Democracy has been part of the mechanism by which the power of the people has influenced the way our lives have improved, through universal suffrage, unions, movements, statutes and laws for equality and justice. When enough people have demanded, shouted, demonstrated and agitated for change, democracy has acted as a rough and ready tool to ensure we got that change. Up to a point.

Now we’re at that point (some would say, well beyond it). Gradually, since the Thatcher era (when Capitalism began to run out of steam) push has come to shove, and the progressive evolution of society is being halted and rolled back. Johnson, like Trump (and there are plenty of others at the moment) is seizing the narrative of populism and using it to promote a right-wing elitist agenda. The problem with this version of populism is that it’s essentially, fairly-and-squarely, Proud To Be Britishly democratic. As the hideous Brendan O’Neill wrote recently in Spiked magazine (itself part of a network of new rightists, the ‘voice of the people’ as funded by American billionaires):

“This cognitive dissonance – to be briefly generous – was summed up in placards being carried by numerous people. The text said: ‘Defend democracy… Stop Brexit.’ And there you have it: defend democracy by crushing a massive democratic vote.”

It wasn’t actually ‘a massive democratic vote’ – it was 52% against 48%. It’s an old cliché, but a reliable one, that ‘democracy is two wolves and a sheep voting on what’s for lunch.' That 52/48 split should be a cause for compromise, instead it’s being used as a mandate to allow the majority to stomp all over the minority. But essentially, O’Neill is right – why are we defending the democratic process that grants the right of people to drag Britain towards being a narrow-minded, provincial, blinkered version of itself, the red-faced bloke in the corner of the Albion Inn dribbling ale down the front of his tatty John Bull costume (from Union Jack Wear, of Clitheroe, Lancashire, pictured above...)?

Yet somehow we keep thinking that our version of democracy, like our version of ‘the news’, is worth defending. It isn’t. British Democracy comes with in-built checks and balances to ensure that the same old elites retain power. It ensures that, should the power swing toward the people, there are enough loopholes for those rich white men to climb through. In my lifetime I’ve seen how we can get better as people – more co-operative, less racist, less sexist, more tolerant, less bigoted. And I’ve also watched recently as all those progressive steps have been attacked and stripped back. Health, education, transport, culture, utilities, all the stuff we gained, it’s all now up for grabs, sold off and asset-stripped – all under the auspices of successive Conservative and Labour governments. What Pfeffel Johnson is doing, backed by his crew of loathsome public school lizards, is just more of the same, more shoring up the elite’s power within a framework we still call democracy.

Ghandi said:

“What difference does it make to the dead, the orphans and the homeless, whether mad destruction is wrought under the name of totalitarianism or in the holy name of liberty or democracy?”

Yesterday I listened to the detestable and odious Jacob Rees-Mogg on Radio 4 being intellectually cuddled by the BBC’s arch-Tory presenter John Humphries. Much as I recognised that Rees-Mogg’s defence of Pfeffel Johnson was obnoxious and repellant, what was worse was detecting the utter smugness of someone who knows that democracy is firmly on his side. This jumped-up Lord Snooty was, as if we need reminding, elected to serve by a democratic mandate of the good people of North East Somerset.

“Democracy means simply the bludgeoning of the people by the people for the people.”

Oscar Wilde

The point of all this is to reiterate that there are higher principles to defend than democracy, at least the democracy we have right now, the democracy that allows Rees-Mogg and the rest to securely act in its name. And by ‘act’, I include all the acts that allow a democratically-elected government to brutalise, marginalise, evict, humiliate, punish, rob and murder so many of its citizens in the name of austerity and welfare reform. The higher principles we need to defend start with equality, freedom, respect, honesty and opportunity. They end when the last Tory cabinet millionaire is strung up by the last Eton school tie.

Rouse, Ye Women! Why Preaching To The Converted Isn't An Insult

28 March, 2019

“Preaching to the choir actually arms the choir with arguments and elevates the choir's discourse.” (Dan Savage)

So the argument is – and it’s an argument I’ve had to deal with all my working life – that making political art is simply ‘preaching to the converted’. Playing to the crowd. That sharing our ideas is worthless unless we’re sharing them with those who profoundly disagree with us.

In response I’d say that now, more than ever, isn’t the time to be trying to ‘convert’ the xenophobes and bigots who’d have us walking backwards into a world of sepia-tinted historic ignorance and small-mindedness. For one thing, I’m getting older and I just haven’t got time to bicker (online or otherwise) with those I have very little in common with. The people I’m interested in talking (and singing) to are the people who, like me, have been battered by Big Politics and its current state of awfulness. Battered by the way so much of social media has become a playground for hateful name-calling, misogyny and arrogance. Battered by failing democracy. Battered by the worldwide rise in right-wing populism. Battered by the cynical careerism of those in power and battered by the idiocy of those who believe, accept and follow them.

No, what I want to spend my time doing is reminding myself of the good stuff, the good people. Remembering that when good people gather we can feel energised and motivated. Rebecca Solnit writes:

‘The majority of Americans, according to Gallup polls from the early 1960s, did not support the tactics of the civil rights movement, and less than a quarter of the public approved of the 1963 March on Washington. Nevertheless, the march helped push the federal government to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act. It was at the march that Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech — an example of preaching to the choir at its best. King spoke to inspire his supporters rather than persuade his detractors. He disparaged moderation and gradualism; he argued that his listeners’ dissatisfaction was legitimate and necessary, that they must demand drastic change.’

Chapel Allerton is a well-off suburb of Leeds, which local estate agents refer to as ‘the village’. It’s not a village, it looks broadly the same as a lot of the rest of Leeds – higgledy-piggledy terraced housing and semi-detached garden estates, the occasional pub and one main bus route along the high street. Chapel Allerton's Seven Arts is a small tidy venue with sofas in the bar and lots of posters on the walls. It’s here that touring theatre group Townsend Productions are performing their ‘folk-ballad-opera’ based on a historic strike by 1000 women chain makers in the West Midlands in 1910.

It’s a stirring story and a stirring re-telling of the story, with music written by John Kirkpatrick, and the cast of three make a solid thumping fist of bringing history alive. Neil Gore plays the authority-figure as Bryony Purdue and Rowan Godel run cast-iron rings around him. Bryony plays union organiser Mary Macarthur; Rowan plays chain maker Bird. Both sing and harmonise beautifully, setting melodic singalongability (if it's not a word it should be) against righteous anger.

It’s history, but it’s also plainly relevant, and the audience lap it up – the non-stop Brexit news coverage we’ve all left behind to come here tonight is so sense-dullingly, arse-clenchingly annoying that the women’s raised fists and catchy choruses are a relief. Just being there in an audience of (presumably) like-minded people is a welcome respite from the puke-making bitchiness of Parliamentary politics.

And it’s this sense of escape that is so valuable right now. It’s not an escape from what’s going on, it’s an escape from the endless volley of undigested hatred surrounding what’s going on. A top-level lack of dignity and honesty that typifies current British and US politics.

“To win politically, you don’t need to win over people who differ from you, you need to motivate your own. There are a thousand things beyond the fact of blunt agreement that you might need or want to discuss with your friends and allies. There are strategy and practical management, the finer points of a theory, values and goals both incremental and ultimate, reassessment as things change for better or worse. Effective speech in this model isn’t alchemy; it doesn’t transform what people believe. It’s electricity: it galvanizes them to act.”

(Rebecca Solnit)

During the 1990s I started to think that marches and big demonstrations were simply a tedious duty. I felt like I’d been traipsing meekly around London landmarks for long enough, and that none of it felt effective or useful. Too many SWP placards, too many megaphone chants. But quite recently, after Trump’s travel ban on Muslem-majority countries was introduced in the US, I joined a hastily-arranged demonstration in Leeds which felt different – it was made up of mainly young people with their own home-made signs and we-don’t-give-a-damn attitude, and I remembered why these demonstrations are important: they’re not for changing the minds of those we demonstrate against, they’re for bringing us together and sensing our own strength. In an age where it seems that we click our way through life, a lot of young people won’t have experienced the physical, noisy, not-quite-predictable thrill of gathering together to shout and sing and make ourselves heard. It can be powerful and intoxicating, and it can send us home wanting to do more.

“I may be preaching to the choir, but the choir needs a good song.”

(Michael Moore)

Townsend Productions have a reputation for touring small-scale theatre around the country, telling incredible stories of resistance and rebellion. What they provide is a space for people to laugh together, sing together, feel stimulated, empowered and motivated. There’ll be a handful of people in every audience that might not agree with the general political thrust of the play – and maybe they’ll be won over by seeing a great story, well told. But if they don’t, no matter. Plays like ‘Rouse, Ye Women’ are important, because they belong to us and we need to hear these stories, we need to sing these songs. To sustain us. And we need them in places like Seven Arts – not just on the TV – to remind us of communality. A shared experience of the invigorating power of live theatre.

And to finish... one more quote from Rebecca Solnit:

“To dismiss the value of talking to our own is to fail to see that the utility of conversation, like that of preaching, goes far beyond persuasion or the transmission of information. At its best, conversation is a means of accomplishing many subtle and indirect things.”

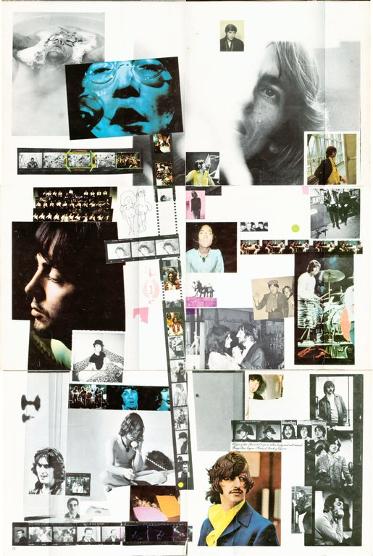

The White Album, Ex/Mint Condition

27 November, 2018

When I wasn’t long into my teens, still obsessed with football but gradually excited by pop music – particularly Alice Cooper’s ‘School’s Out’ – my friend Phil Preston, who lived at the bottom end of our street, showed me a pop magazine with a pull-out poster of The Beatles. This must have been some time in 1973, so it was several years after the band had split up. I remember they were bearded and had long hair, and that I couldn’t tell the difference between them. But I was curious – I couldn’t connect this bunch of hairy blokes with my patchy and jumbled memory of those early hits I’d heard on the radio in our old kitchen. I asked around and found a lad at school who said he had a Beatles album that he’d record for me on cassette.

A week later I had a copy of the White Album on cassette tape (TDK C120), and what I remember most about it was that he’d recorded it with a microphone placed somewhere in the vicinity of his record player’s speakers; I wasn’t put off by the sound of his dad shouting him to come for his dinner halfway through ‘Martha My Dear’ or the noise of passing traffic on his front street punctuating ‘Savoy Truffle’ but I was utterly bemused by the fact that, before each vinyl side commenced, he had leant into the mic and recorded himself declaring “Side one!”, “Side two!” etc.

That Christmas my Grandma and Grandad gave me £5 to buy my own present and off I went to the Record Exchange on Standish Street in Burnley, all patch pockets and budgie shirt, feather cut and aviator specs, to buy the album for real. At this point I didn’t realise that the Record Exchange was to become my church. It wasn’t just the stacks and stacks of second hand records, it was the smell of the sleeves mixed with the ciggie smoke, the shock of the new and unknown, the thrill of discovery. They had a copy of the White Album (yeah I know it’s actually called ‘The Beatles’) stickered as ‘Ex/Mint condition’ with the poster and the photographs inside. It was the first album I ever bought. It was £4. I had a quid left to ‘put towards’ a pair of shin pads.

Fifty years later and the White Album is re-released, remixed and with a zillion extra tracks. I was going to get it for Xmas but I couldn’t wait. I think my Grandma and Grandad would have approved (though back then I couldn’t play ‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’ in earshot of my Grandma. Y’know, with all that “my-finger-on-your-trigger” malarkey). I’ve listened to the whole thing now – five CDs, including demos and rehearsals and whatnot – but I don’t know what I’m supposed to do with the Blu-Ray disc that’s in there. I’m not sure I have anything to actually play it on. What is it? A film? More music?

It’s hard to be objective about the White Album. It’s my Desert Island Disc, in all its sprawling, idiosyncratic weirdness. It has been since the day I took it home and listened to it properly, positioning myself in front of my mum and dad’s stereogram, a teak-finish cabinet with speakers built into each slatted wooden side, with a record player that would stack 45s under its spindle and harshly drop them onto the turntable, one at a time.

What the White Album did was it taught me that music – pop music, at least – could be an adventure. It could be this and that, that and this, heavy, light, happy, sad, pleasantly melodic or uncompromisingly challenging. How could ‘I Will’ and ‘Revolution No 9’ exist in the same cultural universe, never mind on the same record?